Description

“IT IS VERY EXTRAORINDARY, IF THE HEAD OF THE MONEY DEPARTMENT OF A COUNTRY, BEING UNPRINCIPLED ENOUGH TO SACRIFICE HIS TRUST AND HIS INTEGRITY …SHOULD HAVE BEEN DRIVEN TO THE NECESSITY OF UNKENNELING SUCH A REPTILE TO BE THE INSTRUMENT OF HIS CUPIDITY…”: RARE FIRST EDITION OF HAMILTON’S OSERVATIONS ON CERTAIN DOCUMENTS, IN WHICH HE CONFESSES TO HIS AFFAIR WITH MRS. REYNOLDS

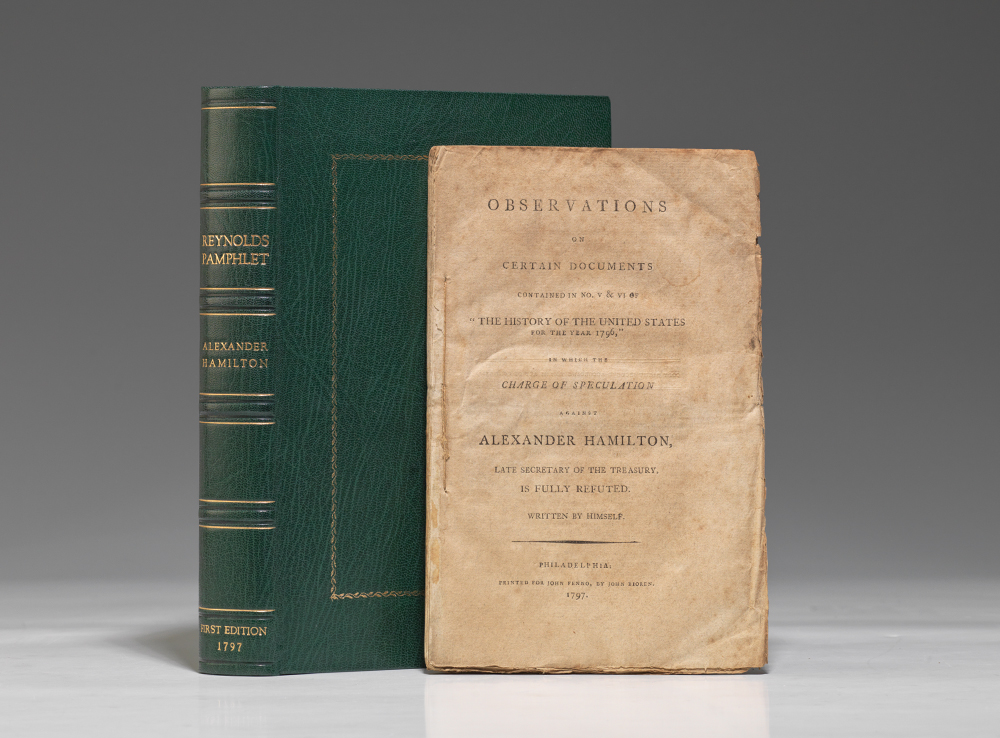

HAMILTON, Alexander. Observations on Certain Documents Contained in No. V & VI of “The History of the United States for the Year 1796,” in which the Charge of Speculation against Alexander Hamilton, Late Secretary of the Treasury is Fully Refuted. Philadelphia: Printed for John Fenno, by John Bioren, 1797. Octavo, unbound, stitched as issued, uncut and unopened. Housed in a custom chemise and half morocco slipcase.

Rare first edition of the infamous “Reynolds” pamphlet, in which Hamilton explicitly shared the details of his affair with Maria Reynolds and the blackmail by her husband, in order to prove himself innocent of the charges of corrupt speculation levied in pamphlets V and VI of James Callendar’s History of the United States for the Year 1796. An exceptional uncut and unopened copy with the original stitching

“On Dec. 15, 1792, James Monroe and two other members of Congress stepped through Alexander Hamilton’s door, ready to torpedo the powerful treasury secretary’s career… The three men believed they had uncovered a financial scam linking Hamilton to a pair of shabby fraudsters, James Reynolds and Jacob Clingman. Notes in Hamilton’s own handwriting to Reynolds and his wife seemed to back up the allegation. Monroe and the two others—Rep. Frederick Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania and Rep. Abraham B. Venable of Virginia—had already drafted a letter to President George Washington outing the Cabinet member. The house call was only a sign of respect before exposing Hamilton to the long knives of public scorn. As Hamilton would later write, the three politicians ‘introduced the subject by observing to me that they had discovered a very improper connection between me and a Mr. Reynolds.’ The treasury secretary, however, cut them short. They had it wrong, he explained. He was not involved in financial duplicity, but an extramarital affair with Reynolds’s wife, Maria. The woman’s husband knew of the affair, forcing Hamilton—one of the most powerful figures in the fragile republic—to fork over hush money. ‘Another man might have been brief or elliptical,’ Ron Chernow wrote in his biography. ‘Instead, as if in need of some cathartic cleansing, Hamilton briefed them in agonizing detail…It was as if Hamilton were both exonerating and flagellating himself at once.’ Realizing they were dealing with an affair of the heart, not the state, Monroe, Muhlenberg and Venable pledged to stay mum. The letter to Washington went unsent…

“The affair eventually went public in 1797 as part of a complex political chess match between Hamilton and his enemies in Thomas Jefferson’s Republican Party. That year, a pro-Jefferson writer named James Callender published a series of pamphlets, The History of the United States for 1796. The text revived accusations that Hamilton, now out of the Cabinet, had engaged in official misconduct with Reynolds and Clingman. The pamphlet suggested the romance between Maria and Hamilton was a cover story for shady financial dealings. Hamilton was in a tight spot. Five years earlier, cornered with the allegations by Monroe and the others, he had opted for disarming honesty. Now, with the Reynolds affair again circulating, he did the same on the public stage with a preemptive strike that would allow him, as the phrase now goes, to put his own spin on everything.” (Kyle Swenson).

Eventually “Hamilton publicly announced that he would defend his honor as an officer of state by explaining the whole affair in a pamphlet. His friends pleaded with him, insisting that he could only harm his party, his family, and himself by such a course…Hamilton was obdurate; nothing was more important than his reputation as an incorruptible public servant…The pamphlet that appeared in late August…is an astonishing production…The charge against him, he said, was ‘a connection with one James Reynolds for purposes of improper pecuniary speculation. My real crime is an amorous connection with his wife for a considerable time, with his privity and connivance, if not originally brought on by a combination between the husband and wife with the design to extort money from me.’ Reynolds, he said, was ‘an obscure, unimportant, and profligate man.’…It is very extraordinary, if the head of the money department of a country, being unprincipled enough to sacrifice his trust and his integrity, could not have contrived objects of profit sufficiently large to have engaged the co-operation of men of far greater importance than Reynolds, and with whom there could have been due safety, and should have been driven to the necessity of unkennelling such a reptile to be the instrument of his cupidity.’

“To show that his communications to and from Reynolds pertained to blackmail and not to speculation with Treasury funds, Hamilton printed the twenty Reynolds letters, which had not been available to Callender. He added some thirty other documents… He said that he had deposited all the original documents with William Bingham in Philadelphia, where any gentleman might inspect them. (Bingham, who had not been consulted later said that he had never received the papers. All, including the Reynolds letters, have disappeared.) When the work appeared, Hamilton’s friends were appalled. ‘What shall we say…’ Webster wrote, ‘of a man who has borne some of the highest civil and military employments, who could deliberately … publish a history of his private intrigues, degrade himself in the estimation of all good men, and scandalize a family, to clear himself of charges which no man believed…’ General Henry Knox wrote to General David Cobb, ‘Myself and most of his other friends conceive this confession humiliating in the extreme, and such a text as will serve his enemies.’ Hamilton’s enemies, of course, were delighted. They simply ignored his points of defense, continued their charges of speculation in public funds, and now bore in on all the new openings Hamilton had given them. Madison, writing to Jefferson, called the publication ‘a curious specimen of the ingenious folly of its Author.’ Callender wrote Jefferson, ‘If you have not seen it, no anticipation can equal the infamy of this piece. It is worth all that fifty of the best pens in America could have said against him. …’ Jefferson observed that Hamilton’s admission of adultery seemed ‘rather to have strengthened than weakened the suspicions that he was in truth guilty of the speculations.’…As an ultimate insult the Antifederalists printed a second edition of Hamilton’s pamphlet, without alteration or addition, at their own expense” (Robert C. Alberts). The Reynolds pamphlet is not included in the edition of his works published in 1810, or in the one authorized by the Congress in 1850″ (Evans 82222). This first edition is known to be extremely scarce. One reason could be, as Sabin noted, that “this edition was afterwards bought up by Hamilton’s family and destroyed; however, we have been unable to find the source of that claim” (Sabin 29969). Howes H120. Evans 32222. Sabin 29970. Ford 64. Reese, Federal Hundred 68.

Faint evidence of dampstain in the lower margin of ten leaves. An exceptional uncut and unopened copy in near-fine condition.