Description

“I HOPE WE SHALL NEVER SACRIFICE OUR LIBERTIES… LET US NOT MISTAKE WORDS FOR THINGS, NOR ACCEPT DOUBTFUL SURMISES AS THE EVIDENCE OF TRUTH. LET US CONSIDER THE CONSTITUTION CALMLY AND DISPASSIONATELY…”: THE “EPIC” 1788 NEW YORK DEBATES ON THE RATIFICATION OF THE CONSTITUTION, LED BY ALEXANDER HAMILTON’S “BRAVURA PERFORMANCE” FOR THE FEDERALIST SIDE

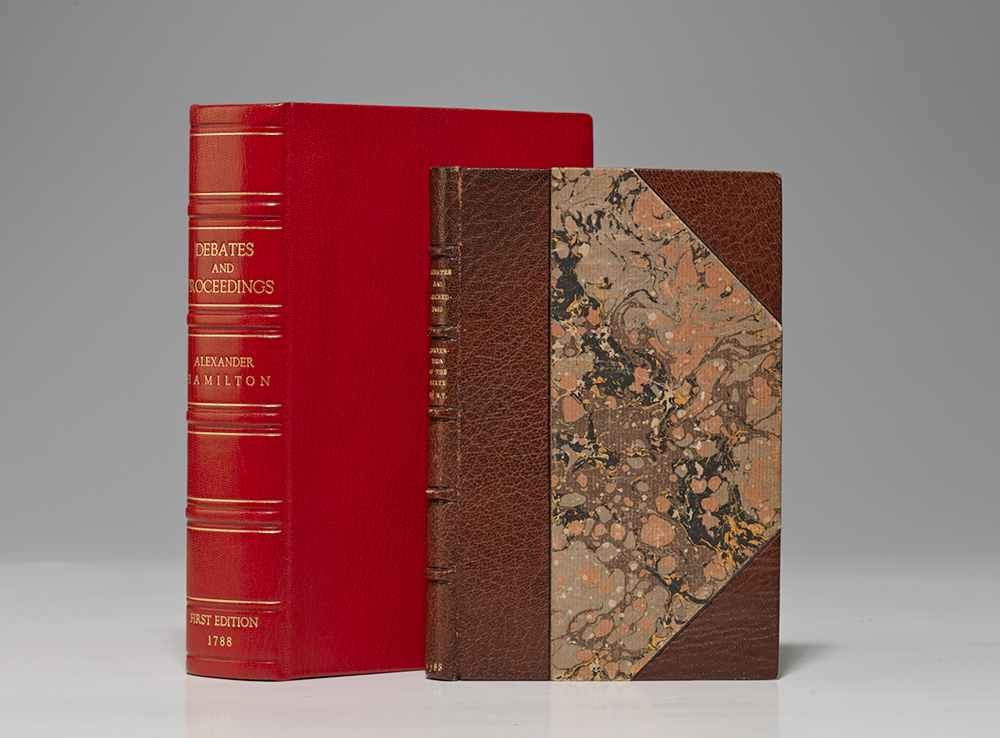

HAMILTON, Alexander. Debates and Proceedings of the Convention of the State of New-York. assembled at Poughkeepsie, on the 17th June, 1788. To deliberate and decide on the form of federal government recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia, on the 17th September, 1787. Taken in short hand. New York: Francis Childs, 1788. 12mo, 20th-century three-quarter brown morocco over marbled boards by Sangorski and Sutcliffe, top edge gilt, housed in a custom chemise and quarter red morocco slipcase; pp. [2], ii, [1], 4-144.

Rare first edition of Francis Childs’ important account of the 1788 New York debates on ratifying the Constitution, which features Alexander Hamilton’s “bravura performance” for the Federalist minority, “an exhilarating blend of stamina, passion, and oratorical pyrotechnics.” Childs, the printer of the New York Daily Advertiser, took shorthand notes of the convention debates and published them in book form in this edition, which is “the most complete account of the Convention debates” and “the most complete record of Hamilton’s remarks.”

Here Hamilton argues that the states now share a national interest and culture reflected in the new proposed government (pp. 46-7): “It has been asserted, that the interests, habits and manners of the Thirteen States are different; and hence it is inferred, that no general free government can suit them. This diversity of habits, &c. has been a favorite theme with those who are disposed for a division of our empire; and like many other popular objections, seems to be founded on fallacy. I acknowledge, that the local interests of the states are in some degree various; and that there is some difference in their habits and manners: But this I will presume to affirm; that, from New-Hampshire to Georgia, the people of America are as uniform in their interests and manners, as those of any established in Europe. –This diversity, to the eye of a speculatist, may afford some marks of characteristic discrimination, but cannot form an impediment to the regular operation of those general powers, which the Constitution gives to the united government. Were the laws of the union to new-model the internal police of any state; were they to alter, or abrogate at a blow, the whole of its civil and criminal institutions; were they to penetrate the recesses of domestic life, and controul, in all respects, the private conduct of individuals, there might be more force in the objection: And the same constitution, which was happily calculated for one state, might sacrifice the wellfare of another. Though the difference of interests may create some difficulty and apparent partiality, in the first operations of government, yet the same spirit of accommodation, which produced the plan under discussion, would be exercised in lessening the weight of unequal burthens. Add to this that, under the regular and gentle influence of general laws, these varying interests will be constantly assimilating, till they embrace each other, and assume the same complexion.”

In response to an Antifederalist proposal to allow state legislatures to recall their senators, Hamilton spoke about the dangers of continuing revolution in America and the need for compromise and order to balance the quest for liberty (p. 71): “In the commencement of a revolution, which received its birth from the usurpations of tyranny, nothing was more natural, than that the public mind should be influenced by an extreme spirit of jealousy…The zeal for liberty became predominant and excessive. In forming our confederation, this passion alone seemed to actuate us, and we appear to have had no other view than to secure ourselves from despotism. The object certainly was a valuable one, and deserved our utmost attention: But, Sir, there is another object, equally important, and which our enthusiasm rendered us little capable of regarding.—I mean a principle of strength and stability in the organization of our government, and vigor in its operations. This purpose could never be accomplished but by the establishment of some select body, formed peculiarly upon this principle. There are few positions more demonstrable than that there should be in every republic, some permanent body to correct the prejudices, check the intemperate passions, and regulate the fluctuations of a popular assembly…Without this establishment, we may make experiments without end, but shall never have an efficient government.”

Hamilton gave a “bravura performance” at the convention, and after weeks of intense political sparring and difficult compromises, New York finally became the eleventh state to ratify the Constitution on July 26, 1788. “The final vote of thirty to twenty-seven was the smallest victory margin at any state convention” (Chernow, p. 268). “The New York Ratifying Convention, having approved the Constitution, also voted unanimously to prepare a circular letter to the other states, asking them to support a second general convention to consider amendments to the Constitution. Several other states had also voted for ratification only with a promise that amendments to the Constitution, especially a bill of rights, would be proposed in the first Congress. New York’s ratification message was the longest of any of the state conventions, and proposed 25 items in a Bill of Rights and 31 amendments to the Constitution” (New York Historical Society).

“Francis Childs, the printer of the New York Daily Advertiser, published the most complete account of the Convention debates. Childs took notes in a primitive shorthand and also allowed speakers to review and edit his account of their remarks. The Debates and Proceedings was published on December 16, 1788. The daily reports taper off after July 2, partly because they were taking so much time to prepare” (New-York Historical Society). “The most complete record of Hamilton’s remarks from the beginning of the Convention until June 28 was made by Francis Childs” (Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Founders Online). “From a letter in the Lamb papers (N.Y. Historical Soc.) it appears probable that at least Hamilton, Jay and Lansing revised their speeches, though Francis Childs, the reporter, virtually, in his preface says that no such revision took place” (Ford 103). Without final blank (N6). Sabin 53634, Streeter 1054, Evans 21310, ESTC W4576. With two previous owner’s bookplates on front pastedown, one being Joseph T.P. Sullivan, a lawyer long active in Democratic politics in New York City.

Expert paper repairs to title page, tiny marginal hole to “advertisement” page, not affecting text, a few pages opened roughly. Binding handsome.