Description

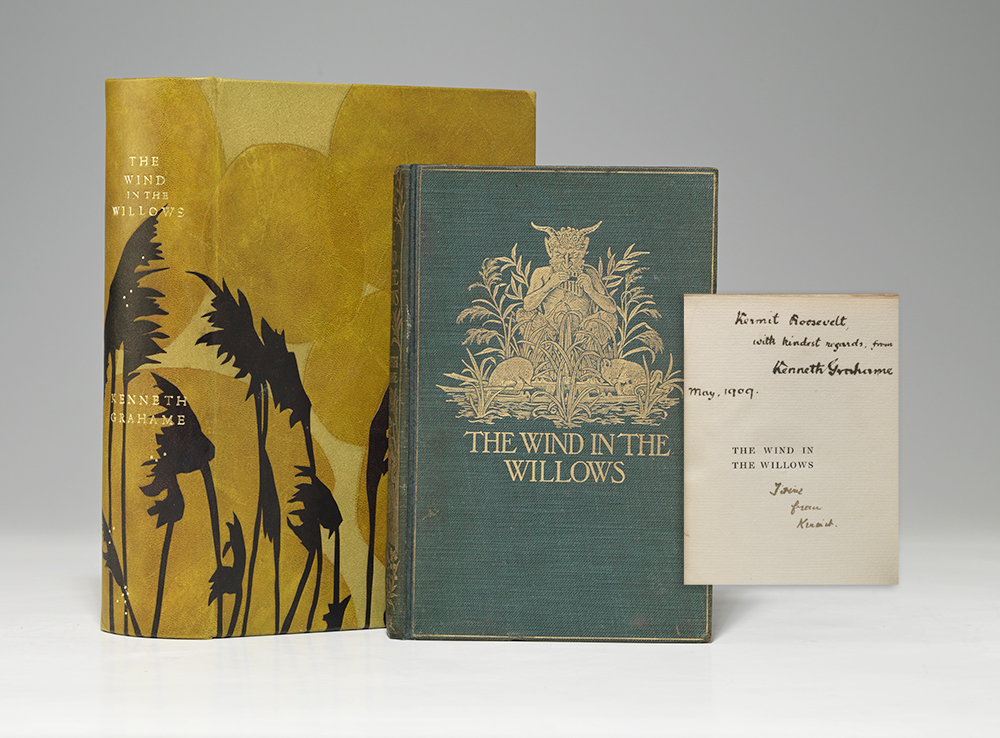

SUPERB ASSOCIATION COPY OF “ONE OF THE MOST ENDEARING BOOKS EVER WRITTEN FOR CHILDREN,” THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS, INSCRIBED IN 1909 BY KENNETH GRAHAME TO KERMIT ROOSEVELT, THE SON OF THE BOOK’S MOST SIGNIFICANT ADVOCATE, PRESIDENT THEODORE ROOSEVELT, WHO HELPED SECURE A PUBLISHER IN THE U.S.

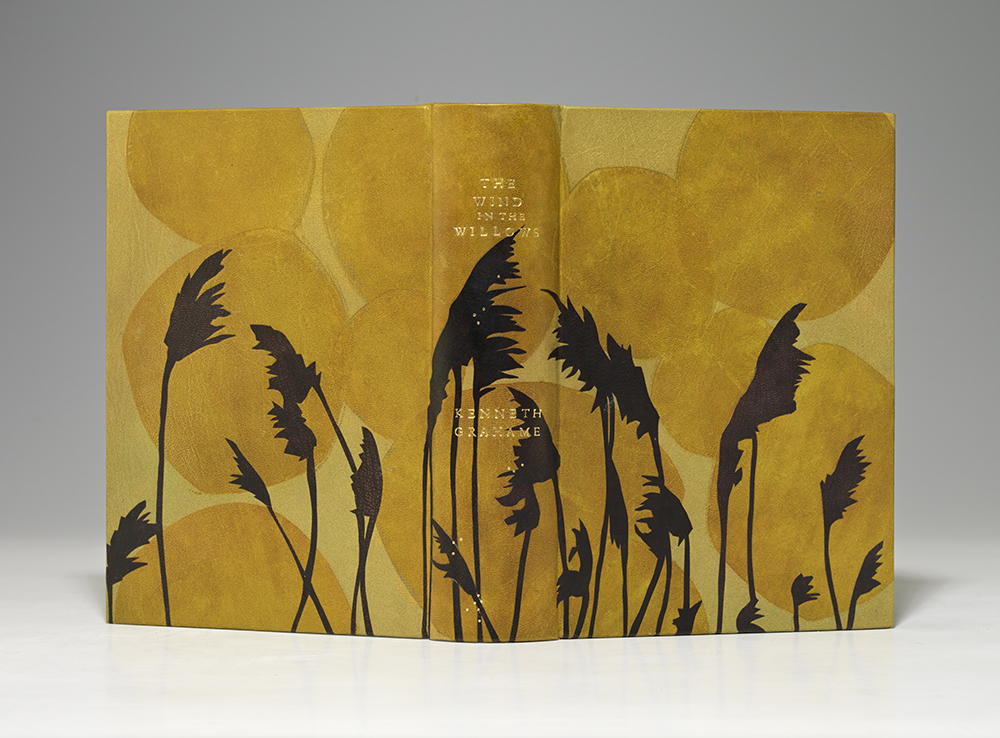

GRAHAME, Kenneth. The Wind in the Willows. London: Methuen, (1908). Octavo, original gilt-stamped pictorial blue cloth expertly rebacked with original spine neatly laid down, retaining original endpapers, top edge gilt, uncut.

First edition of the beloved children’s novel, an important presentation copy, inscribed by the author, “Kermit Roosevelt, with kindest regards, from Kenneth Grahame, May 1909” on the half title, and subsequently inscribed from Kermit to “Titine.” A superb association copy, inscribed to the second son of the book’s staunchest and most significant advocate, President Theodore Roosevelt.

President Theodore Roosevelt was already a deep admirer of Grahame’s work prior to the publication of The Wind in the Willows, and wrote to him on 22 October 1908 anticipating the arrival of the book (“The book hasn’t come, but as I have never read anything of yours yet that I haven’t enjoyed to the full, I am safe in thanking you heartily in advance”). On 17 January 1909, quite enamored with the book, Roosevelt personally wrote to Grahame: “At first I could not reconcile myself to the change from the ever delightful Harold and his associates, so for some time I could not accept the toad, the mole, the water-rat and the badger as substitutes. But after a while, Mrs. Roosevelt and two of the boys, Kermit and Ted, all quite independently, got hold of The Wind in The Willows, and took such delight in it that I felt I might have to revise my judgement. Then Mrs. Roosevelt read it aloud to the younger children, and I listened now and then. Now I have read it and reread it, and have come to accept the characters as old friends; and I am almost more fond of it than your previous books.” Wind in the Willows initially met with contempt from the critics, who were hoping for a third volume in the same style as The Golden Age and Dream Days (“Grown-up readers will find it monstrous and elusive…Children will hope, in vain, for more fun,” wrote the Times critic, and Arthur Ransome called it “a failure, like a speech to Hottentots made in Chinese”), and it was rejected by every publisher, except Methuen, who then only published it on the condition that Grahame would not receive an advance. However, once Roosevelt wrote to Scribners, the American publishers, saying that the book was “such a beautiful thing that Scribner must publish it,” they reversed their earlier rejection, and sales of the book exploded. Following the book’s publication in America in early 1909, and Roosevelt’s letter expressing his sons’ appreciation of the book, it is likely that Grahame sent this inscribed copy to Kermit, then a young man of 20. The following year, when President Roosevelt visited Oxford to give a lecture at the Sheldonian Theatre, one of the few people he requested to meet was Kenneth Grahame, who attended the lecture and spoke with him afterwards.

“Unquestionable is the permanence, as an inspired and characteristically English contribution to children’s literature, of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows… one of the most endearing books ever written for children… Part of the secret success of the book is that its appeal is ageless and parents never tire of reading it aloud. Like all great books it is inexhaustible” (Eyre, 62). Grahame created his classic as a series of bedtime stories for his four-year-old son Alastair, who was known as Mouse; yet it also became “in many respects an elegy for the old idyllic English rural life which Grahame could now see was passing away forever” (Carpenter & Prichard, 218). C.S. Lewis praised it as “a perfect example of the kind of story which can express things without explaining them” (Carpenter, 168). Without extremely rare original dust jacket. Pierpont Morgan Children’s Literature 269. Kermit Roosevelt in turn presented this book to “Titine”: the socialite Celestine Hitchcock Peabody (1892-1935), daughter of Thomas Hitchcock (1860-1941), an outstanding polo player, who, in 1892, founded the Palmetto Golf Club in Aiken, South Carolina—a fashionable winter playground for many of the country’s wealthiest families, such the Vanderbilts and the Whitneys. Theodore Roosevelt, a family friend of the Hitchcocks and fellow foxhunter, had a house nearby in Oyster Bay where he often spent the summer with his family. Just three years younger than Kermit, it is likely the two were childhood friends. Celestine married New York City architect Julian L. Peabody and died with him in January 1935, in the sinking of the S.S. Mohawk off the coast of New Jersey.

Occasional spot of foxing to interior; minor rubbing to corners, cloth clean, gilt bright. A very desirable presentation-association copy of this children’s highspot, extraordinarily difficult to find signed or inscribed.