Description

“THE PENMAN OF THE REVOLUTION… AS PREEMINENT AS WASHINGTON IN WAR, FRANKLIN IN DIPLOMACY”: AN EXCEPTIONAL RARITY, FIRST EDITION, FIRST PRINTING OF JOHN DICKINSON’S LETTERS FROM A FARMER, 1768, “UNEQUALED IN POPULAR FAME UNTIL PAINE’S COMMON SENSE”

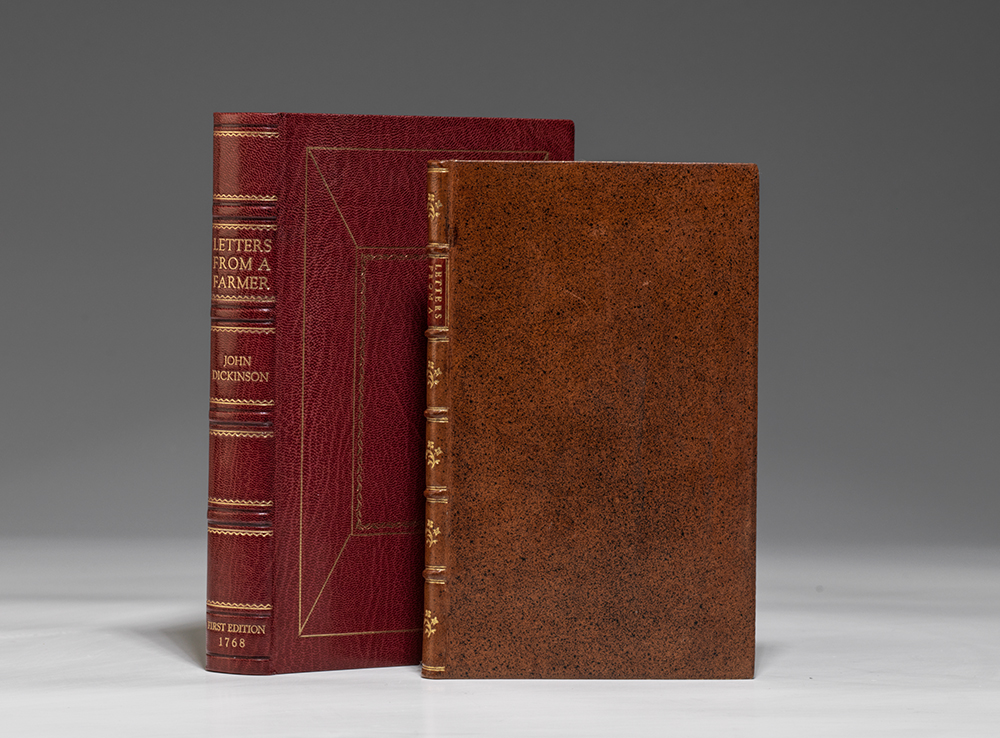

(AMERICAN REVOLUTION) (DICKINSON, John). Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, To the Inhabitants of the British Colonies. Philadelphia: Printed by David Hall, and William Sellers, 1768. Octavo, period-style full speckled calf gilt, red morocco spine label; pp.(1-2), 3-71 (1).

First edition, exceedingly rare first printing, of the seminal first appearance in book form of the Farmer’s Letters by Founding Father Dickinson—”a leader of the Revolutionary movement from its inception”—a clarion call for American liberty, heralded as “the most important political writing of the revolutionary period,” anonymously issued in Philadelphia by publisher David Hall, longtime partner of Benjamin Franklin, who declared Dickinson’s Letters to be “the greatest pieces ever wrote on the subject.” This copy is distinguished by very distinctive association in containing the bookplate of R.T.H. Halsey, a founder of the American Wing of New York’s Metropolitan Museum.

“John Dickinson has been aptly termed the ‘Penman of the Revolution.’ In the literature of that struggle, his position is as preeminent as Washington in war, Franklin in diplomacy” (Leicester Ford, Political Writings V.I:ix). He was “a leader of the Revolutionary movement from its inception—author of the Declaration of the Stamp Act Congress and of the Farmer’s Letters, drafter if not sole author of both the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking up Arms and of the Articles of Confederation” (Bailyn, Pamphlets, 660). In September 1767, as news of Britain’s punitive Townshend Acts reached the colonies, “Dickinson took up his pen to defend American liberty. In 12 letters signed ‘A Farmer’ he made a bold step in clarifying and strengthening the colonists’ claims” (Kaestle, Public Reaction, 323). His Letters “ran through the colonies like wildfire, furnishing a common fighting ground to all” (Leicester Ford, ix), and making an impact “unequaled in popular fame until Paine’s Common Sense” (Kaestle, 326). Historian Jane Calvert concurs, noting: “Dickinson was vital to the founding of the U.S.” (Delaware Today).

By targeting Parliamentary taxation, as well as Britain’s suspension of the New York Assembly, Dickinson’s Letters “implicitly approached the larger and potentially revolutionary question: What is an American?” To Dickinson, “the obligation to protest springs from the bonds that unite past, present and future generations in the sacred labors of family and community.” In affirming American rights, he demonstrates “that the expense of complying with any regulation was a tax to the extent of the expense, and that right of the colonial Assemblies to resist must be reserved. The punitive dissolving of the Assembly in New York was a most flagrant assault on this fundamental safeguard of liberty.” This profoundly influential work also affirms “how rich and multi-faceted an event the American Revolution was… [it] loosened the fabric to permit other success stories, other paths to legitimacy, other dreams of the good life” (Johannesen, John Dickinson and the American Revolution).

This exceedingly rare first edition of his Letters sounds the core elements of colonial resistance: “the fundamental threat to liberty posed by executive power over the convening of assemblies (Letter I), the danger of losing the power of voluntary taxation (primarily Letters VII, VIII and IX), with the consequent horrors of corruption, proliferation of office, and standing armies (Letter X), and, most important, the inevitability of worse tax measure to come if the colonists allowed a precedent to be set (Letters II, IV, X, XI and XII)… he appealed to theories firmly embedded in American political thought, and he supported his arguments with examples from ancient Greece to contemporary Ireland and with authorities from Tacitus to Pitt… it is clear from the public response that the Letters voiced not one but a variety of the Americans’ fears. So Franklin, despite his qualms, presented the Letters to the English public as ‘the greatest pieces ever wrote on the subject,’ containing ‘the great Axioms of Liberty’ and an ‘American System of Politicks.’ The comprehensiveness of the Letters… made Dickinson’s message keenly relevant to Americans in all the colonies” (Kaestle, 331-33). He fundamentally demonstrated that “the king and Parliament were making radical innovations and that the Americans were defending ancient traditions and rights… As a writer, he was masterful. As an orator, he was adjudged by John Adams (who disliked him) to be the equal of Patrick Henry and there could be no higher praise than that… the celebrity that Dickinson won through the Letters ensured that he would be the principal pensman for the 1st and 2nd Continental Congresses… He wrote most of their petitions to Parliament, to the Crown, and to the British people, including… with Jefferson as coauthor, the bellicose Declaration on the Causes and Necessity of Taking up Arms (McDonald, Most Underrated Founder).

Dickinson ranks, above all, as “a radical in the vital sense in which the Revolution itself was radical” (Bailyn, 662). This nearly peerless work stands as “the most important political writing of the revolutionary period… a critical source to understand if one seeks to comprehend the political thought of the American Revolution” (Webking, American Revolution, 41-3). Dickinson wrote the entire series of letters as a unit prior to their anonymous appearance in colonial newspapers: “first in the Pennsylvania Chronicle between November 30, 1767 and February 8, 1768″ (Adams, American Independence 54a), and concluding in their serialized appearance in Savannah’s Georgia Gazette beginning January 27, 1768. When this first edition was anonymously published by Hall and Sellers in Philadelphia on March 18, 1768, the editor of the Pennsylvania Chronicle estimated this first printing “would sell ‘several hundred copies'” (Kaestle, 326). ESTC W19245. Evans 10875. Adams, American Controversy 68-7a. Sabin 20044. This copy contains an especially notable provenance in containing the bookplate of Richard Townley Haines Halsey and H.E. Halsey. Richard T.H. Halsey was a “founder of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum in New York… a trustee and chairman of the committee on American Decorative Arts at the museum… vice president of the art commission for the City of New York… an avid collector of Americana,” and a prominent member of the Walpole Society and the Grolier Club. The additional initials on the bookplate of “H.E. Halsey” likely refer to one of his first two wives, whose names are unknown (Winterthur Library).

Text generally fresh; partially excised contemporary owner signature above title page and first text page expertly restored, affecting just three words on page 4.