Description

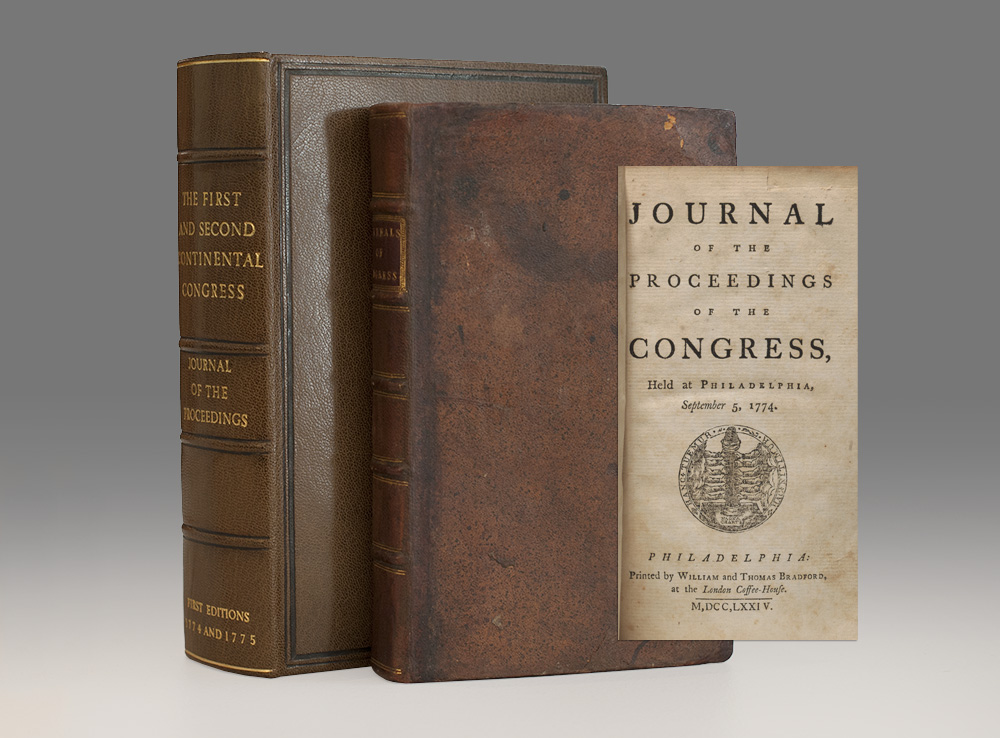

“A BOOK OF THE GREATEST RARITY”: EXCEPTIONALLY IMPORTANT 1774 FIRST ISSUE OF THE FIRST FULL ACCOUNT OF THE FIRST CONTINENTAL CONGRESS, ONE OF THE EARLIEST PUBLICATIONS OF THE NEW GOVERNMENT, INCLUDING THE “DECLARATION AND RESOLVES” ON COLONIAL RIGHTS, A PRECURSOR OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE—BOUND TOGETHER WITH THE EQUALLY RARE 1775 JOURNAL OF THE SECOND CONTINENTAL CONGRESS, INCLUDING JEFFERSON’S IMPORTANT “DECLARATION OF THE REPRESENTATIVES… SETTING FORTH THE CAUSES AND NECESSITY OF THEIR TAKING UP ARMS”

(CONTINENTAL CONGRESS). Journal of the Proceedings of the Congress, Held at Philadelphia, September 5, 1774. BOUND WITH: Journal of the Proceedings of the Congress, Held at Philadelphia, May 10, 1775. Philadelphia: Printed by William and Thomas Bradford, 1774, 1775. Two volumes bound in one. Octavo, contemporary full sheep rebacked, red morocco spine labels; pp. [4], 132; [4], iv, 239. Housed in a custom full leather clamshell box.

First edition, first issue, of the first official journal of the Continental Congress, one of the earliest publications of the American government, “a book of the greatest rarity,” containing the seminal “Declaration of Rights and Resolves” to the King and Parliament on colonial rights, and featuring the famous woodcut design on the title page that represents the first attempt to create a seal to “represent emblematically a united nation” in America. Bound with a first edition of the official journal of the second Congress, from May 10 through September 5, 1775—the activities of this summer, against the background of open conflict in Massachusetts, are among the most dramatic of the Revolutionary era. Together, two of the most fundamental documents of the American Revolution, both very rare.

In response to the Coercive or Intolerable Acts enacted by Parliament from March-June 1774, the colonies united and sent delegates to the First Continental Congress, which met in Philadelphia from September 5 through October 26, 1774. Their objective was to compose a statement of colonial rights, identify the British government’s violation of those rights, and provide a plan that would convince Britain to restore those rights. This is the first publication of the full account of these extraordinary proceedings, published by order of the Congress from the official minutes taken by Secretary Charles Thomson, and printed by William and Thomas Bradford, the official printers to the new government, immediately after the adjournment of Congress. This is also one of the earliest publications of the new government, preceded only by pamphlets containing partial extracts of the proceedings “printed in separate parts and issued as the acts and resolutions occurred. Later they were collected either by sewing together the existing separate publications without alteration or… repaging standing type.” (Adams, American Controversy:244).

The deliberations of the First Continental Congress “were to be confidential; no news of votes and proceedings was made public. But as the work of the Congress gathered momentum, resolutions, declarations and addresses intended for wide circulation were ordered to be printed. “An eager and excited American public was anxious to learn what the unprecedented Congress had accomplished. The printers immediately began to put together the most important public statements, at first consisting of the separate pamphlets they had printed brought together under the title, dated October 27, Extracts from the Votes and Proceedings of the American Continental Congress, and then, to meet the demand, reprinted it as an entity… It took a while longer for the Bradfords to prepare the text of the Journal which was made available to them by Charles Thomson. This was the full report of the actions of the Congress, including, of course, all the documents which had appeared in the Extracts… One touch was added by the printers on the title-page of the Journal. They had a seal designed for the United Colonies. Upon the Magna Charta stands a pillar held by twelve hands and topped by a liberty cap; a motto reads: ‘Hanc Tuemur, Hac Nitimur,’ or, ‘this we defend, by this we are protected… it stands as the first attempt to represent emblematically a united nation” (Wolf, Introduction, Journal of the Proceeding of the Congress).

“On that same busy day after Congress’ adjournment, October 27,… [the Bradfords] issued what is today a book of the greatest rarity, Journal of the Proceedings of the Congress, an octavo of 132 pages, not to be confused with the later serial volumes bearing the same title. If we are to believe the Bradfords’ dating, it was… certainly started that day and continued at a fierce pace. In the Pennsylvania Packet for November 21 is the announcement that the Journal will be published ‘this afternoon… but already one delegate had written back on October 31 that Congress’ proceedings ‘are now in the press, part of which is published.’ And another sent the Journal home as early as November 7. Someone has called this first volume to bear the title Journal the ‘original edition… it contained so much new material, so much new setting of previously printed stuff, that we may believe the Bradfords received Thomson’s minutes as the full record they had been waiting for and building toward, the climax of their astonishingly busy week” (Powell, 45).

The First Continental Congress “evolved into a federal government of a nation at war… Congress faced a delicate task. America as a whole did not want independence; every path to conciliation must be kept open. But Congress had to do something about the Coercive Acts, and also to suggest a permanent solution of the struggle between libertas and imperium” (Morison, 207-8). Foremost in the proceedings was the “Declaration and Resolves,” to the King and Parliament, objecting to the Coercive Acts and asserting the fundamental rights of the colonists, including: “life, liberty, and property”; the rights and liberties granted to English citizens; representation and participation in legislation and government, especially in issues of taxation and internal policy; trial by jury; “a right peaceably to assemble, consider of their grievances, and petition the King,” etc. These important rights and liberties were the defining issues of the revolution and became the foundation of the Declaration of Independence. “The Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress was the direct precursor of the declarations of rights contained in the Revolutionary state constitutions… In the 1774 declaration, the American is emerging from his colonial status… In declaring that the rights of the colonists are natural rights, the Declaration and Resolves anticipates the more famous statement on this issue in the Declaration of Indepenence and prepares the way for the elevation of the rights involved to the constitutional plane” (Schwartz, 64). Also herein is the Address to the People of Great Britain, an Address to the Inhabitants of the Province of Quebec, and an agreement called The Association that called for cutting off imports to and from Britain if the Coercive Acts were not repealed. Congress further passed the resolution to reassemble on 10 May 1775 if colonial rights and liberties had not been restored.

The First Continental Congress met in 1774 with the hope of eventual reconciliation and the recovery of colonial rights and liberties violated by the British government. Those hopes went unfulfilled, and The Second Continental Congress met in May 1775, only a few weeks after open warfare had broken out at Lexington and Concord. By this time everything had changed, and “the point of no return had been reached” (Johnson, History of the American People, 149). The journals capture this essential shift from conciliation to revolution in the actions, debates, and writings of the Second Congress. Among the most important works of the Congress printed in this journal is the July 6, 1775 “Declaration by the Representatives… setting forth the causes and necessity of their taking up Arms,” written by Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson, one of the greatest state papers of the Revolution and an important forerunner to the Declaration of Independence: “Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal resources are great… the arms we have been compelled by our enemies to assume, we will, in defiance of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverance, employ for the preservation of our liberties, being with one mind resolved, to die Freemen rather than to live as slaves.” The journals also include reports on Lexington and Concord, the address to the inhabitants of Canada inviting them to join the other 13 colonies, numerous military matters (including the appointment of Washington as commander in chief of the army), the Olive Branch Petition, the American negotiations with the Six Nations, and other crucial material.

“On 10 May 1775, when all America was buzzing with the news of Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress met at Philadelphia. No more distinguished group of men ever assembled in this country…” The delegates included John Hancock and the Adamses from Massachusetts (“the seat of war”), George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry from Virginia, and Benjamin Franklin and John Dickinson from Pennsylvania. “John Hancock… was chosen president…. Besides creating a provincial army and navy and sending diplomatic agents to Europe, Congress assumed sovereign power over Indian relations… It approved the hot war that had broken out in Massachusetts, adopted the militia besieging the redcoats in Boston as the ‘Army of the United Colonies,’ appointed Colonel George Washington commander in chief, sent Benedict Arnold across the Maine wilderness in the expectation of bringing in Canada as the 14th colony, and authorized other warlike acts….” (Morison, Oxford History of the American People, 215-16). The first issue of the first journal is extraordinarily rare. The second (and more common) issue of the first Journal contains two additional documents, General Gage’s letter and the Petition to the King, which were separately printed by the Bradfords early in 1775, with pages numbered 133-144, and added without a separate title page to the copies on hand of the Journal. The title page bears the famous seal of the Congress, showing 12 hands representing the 12 participating colonies supporting a column topped with a Liberty Cap and resting on the Magna Charta. The Journal of the second Congress, like those of the first, is also quite rare. Bound with both half titles. Howes J263 “b” (notes only 3 copies located); J264, “aa.” Evans 13737, 14569. Contemporary ink ownership inscription on first half title.

Light toning and foxing to text. Contemporary sheep corners expertly restored. A very good copy of these important works, most rare and desirable.