Description

VERY RARE PRESENTATION COPY OF CHARLES DICKENS’ THE PICKWICK PAPERS, BOLDLY INSCRIBED AND SIGNED BY DICKENS WITH HIS CHARACTERISTIC FLOURISH: “NEVER WAS A BOOK RECEIVED WITH MORE RAPTUROUS ENTHUSIASM THAN THAT WHICH GREETED THE PICKWICK PAPERS“

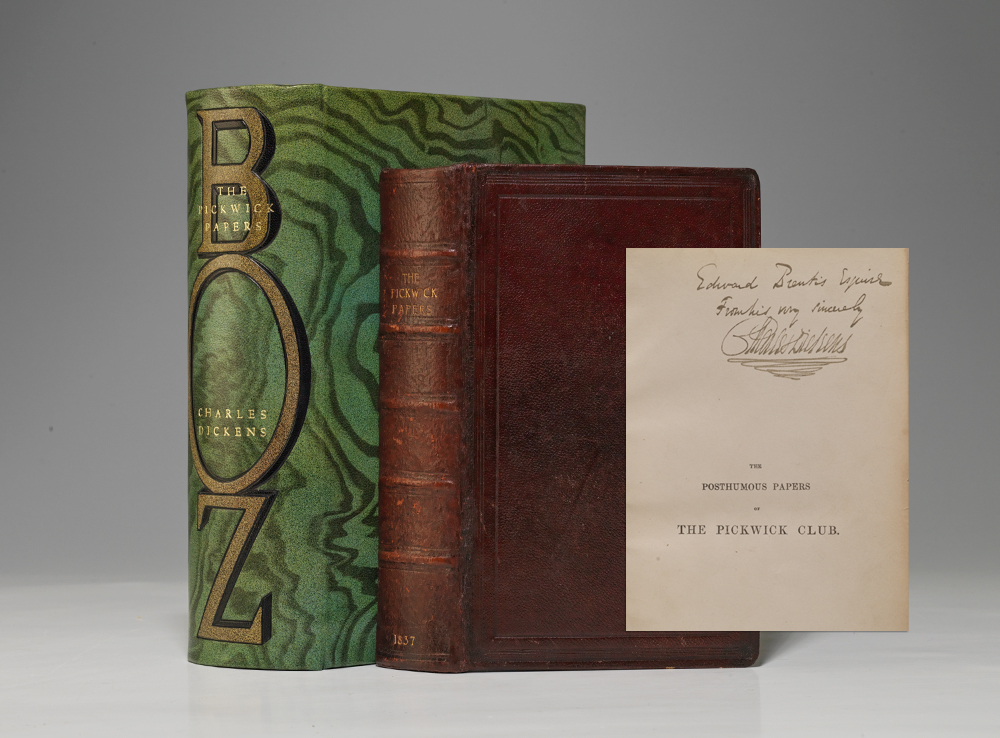

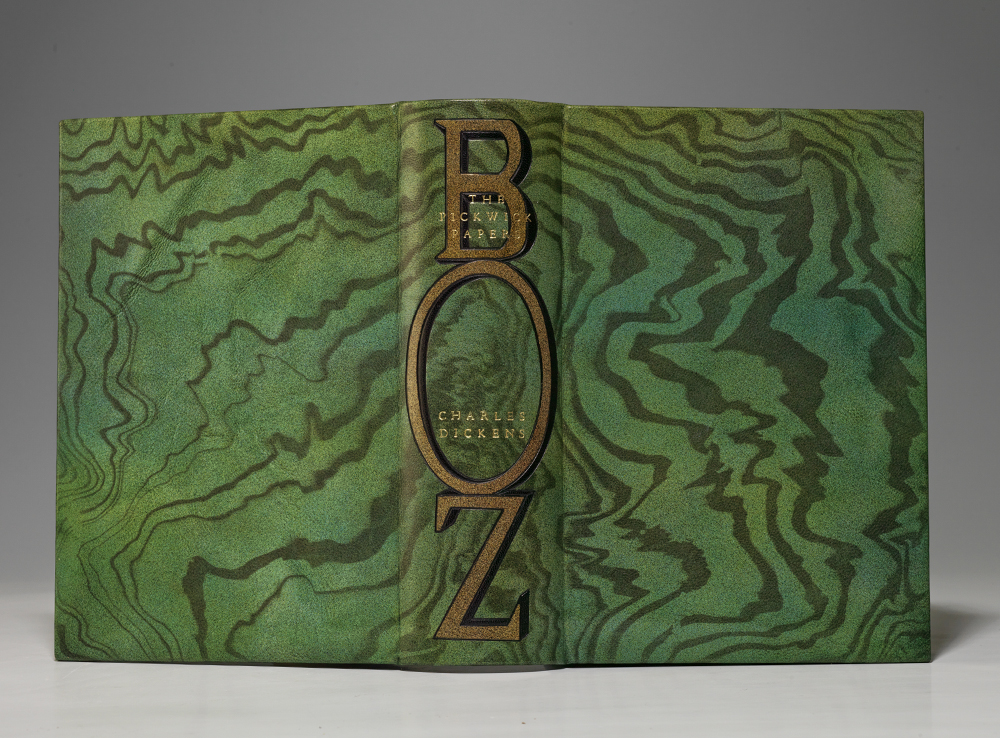

DICKENS, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. London: Chapman & Hall, 1838. Thick octavo, publisher’s deluxe purple pebbled morocco, skillfully rebacked to style, raised bands, endpapers renewed, all edges gilt.

First edition of one of Dickens’ greatest works, very rare signed presentation copy in the publisher’s deluxe morocco binding, inscribed and signed by Dickens with his characteristic bold flourish on the half title, “Edward Prentis Esquire, from his very sincerely, Charles Dickens.” With 43 illustrations by Seymour, Browne and Phiz.

As he often did when presenting copies of his novels to friends and associates, Dickens used a copy in the publisher’s deluxe morocco binding for this presentation. The recipient, painter Edward Prentis (1797-1854) was the brother of the poet Stephen Prentis. They were the sons of Walter Prentis, mayor of Rochester, who owned the 16th-century Restoration House which Dickens knew from childhood and used as a model for Miss Havisham’s house in Great Expectations.

“Charles Dickens is fused in the public imagination with the streets of Victorian London but it was really Rochester and the surrounding area near the Medway River that holds the key to the beloved author’s imagination. The historic Kent location, about an hour from London via train was the childhood home of Dickens before his father was sent to debtor’s prison and Dickens himself to a workhouse. The family lived at Chatham and on walks in the area, Dickens’ father pointed out a large mansion and said, ‘If you were to be very preserving and were to work hard, you might someday come to live in it.’ Dickens did indeed come to live at that house, Gad’s Hill Place, after he found fame. He bought the house in 1856 and lived in it till he died in 1870. The home was close to Rochester, the place that framed characters and places that lives in Dickens’ most famous books, including Great Expectations and The Mystery of Edwin Drood

. Walking the cobbled streets of Rochester, a historic cathedral and castle town,[one] can see building after building with iconic blue plaques that confirm that the quirky, half-timbered houses, the centuries’ old alms and pilgrims’ houses and the pubs and hotels they identify are the same places that fired young Charles’ imagination. Restoration House, for example, a fusion of two medieval buildings, was said to have been the inspiration for the massive, dark, Satis House, haunted by the spectral Mrs. Havisham, in Great Expectations.” (Gretchen Kelly).

It is possible that Dickens knew of Edward Prentis as a child but we think it more likely that he knew him as an adult in connection with Dickens’ circle of friends.. Edward first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1823 and exhibited at the Royal Society from 1826 until 1850. “He painted genre scenes of domestic life, often with allegorical meaning, and his works were accompanied in the exhibition catalogues with quotations from literature” (ODNB). Among the pictures he exhibited at the Society of British Artists were The Nervous Miser (1826), The Wife and the Daughter (1836), and The Folly of Extravagance (1850). One of his works was a scene in the famed Star & Garter Hotel, one of Dickens’ favorite places. “In the 19th century the Star & Garter was the most glamorous hotel in Britain, the haunt of royalty and the literary establishment. John Cloake’s article, ‘That Stupendous Hotel’, described Dickens celebrating the publication of David Copperfield there, with Tennyson and Thackeray among his guests” (Richmond History). In 1841, Prentis painted a dinner scene at the Star & Garter of a party that included several of Dickens’ circle—Tom Beard and John Leech—ass well as Prentis himself, his brother Stephen and George Cattermole. The painting, which became a famous engraving, “depicts a group of gentlemen, well known in the art world, who have been confronted by a bill for a large meal they have just consumed” (Connoisseur, Vol. 187, issue 751-52).

“From a literary standpoint the supremacy of this book has been… firmly established… It was written by Dickens when he was 24 and its publication placed the author on a solid foundation from which he never was removed…. It is quite probable that only Shakespeare’s Works, the Bible and perhaps the English Prayer Book exceed ‘Pickwick Papers’ in circulation” (Eckel, 17). “Never was a book received with more rapturous enthusiasm than that which greeted the Pickwick Papers!” (Allibone I:500). Pickwick was the first title to name the author as “Charles Dickens,” instead of his pen name, “Boz.” Originally issued in 20 parts from April 1836 to November 1837. Chapman and Hall issued Pickwick Papers in cloth for 21s., half morocco for 24s. 6d., and full morocco with gilt edges for 26s. 6d. (Patton, 326). Variant deluxe publisher’s bindings are known, including states in green morocco. Dickens’ bibliographers have generally overlooked the deluxe bindings, with the result that the relative priorities of the variant states are unknown.

This later issue copy has the following textual states: the engraved frontispiece has the stool with six stripes and the signature undivided at left of shield; the vignette title page has “Weller” and is signed “Phiz fect”; the plates are entirely re-etched and do not contain page locations; they are signed, titled, and contain the Chapman & Hall imprint, and the two Buss plates are replaced by two of Browne’s. These are often called later issues (by Smith, for example), but they are the corrected states, made after the monthly parts but in time for first issue in book form as a single octavo volume. Copies with these corrected states were available on publication day in book form, 17 November 1837. The letterpress title page here is also in secondary state, dated 1838, though this need not necessarily imply that this copy was issued in that calendar year. Victorian publishers habitually post-dated books that they hoped would sell well over the Christmas season and into the New Year. Smith I:3. Eckel 17-58. Gimbel A15. Ticket of Young’s Library, Kensington High Street, to foot of front pastedown.

Light foxing to contents, some light marginal oxidization to plates, though less noticeable than often; slight rubbing to board edges, very good condition. A most rare and desirable presentation copy, boldly inscribed by Dickens and in the publisher’s deluxe morocco.