Description

“FROM HIS AFFECTIONATE FRIEND CHARLES DICKENS, CHRISTMAS 1841”: SPLENDID PRESENTATION-ASSOCIATION COPY OF OLIVER TWIST, INSCRIBED BY CHARLES DICKENS AT CHRISTMASTIME TO GREAT FRIEND WILLIAM MACREADY

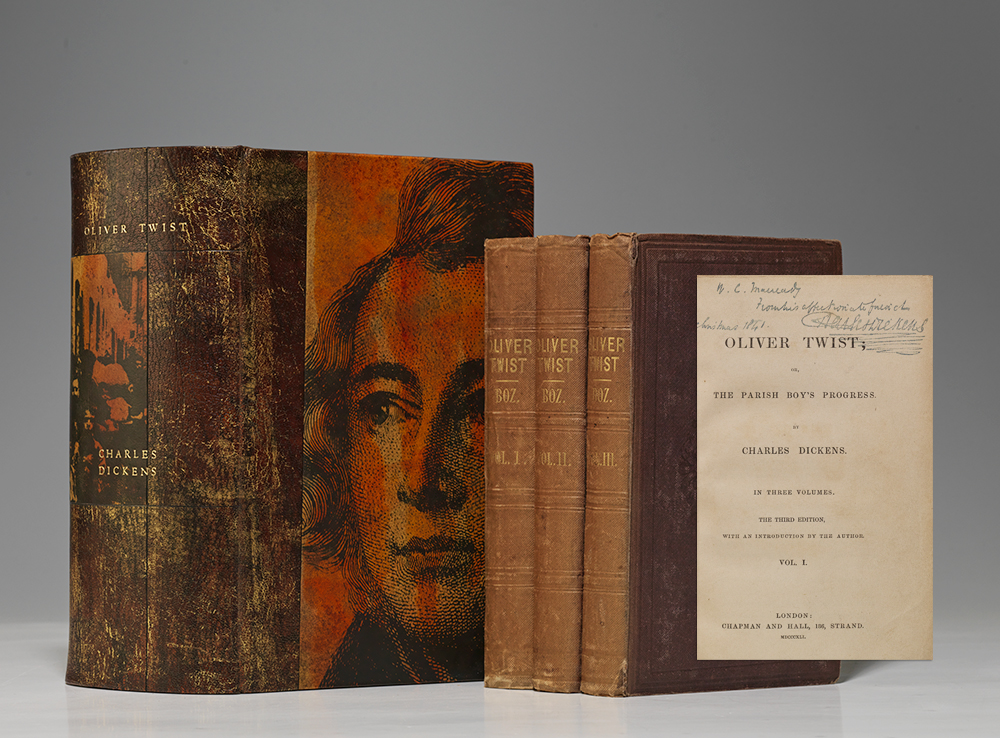

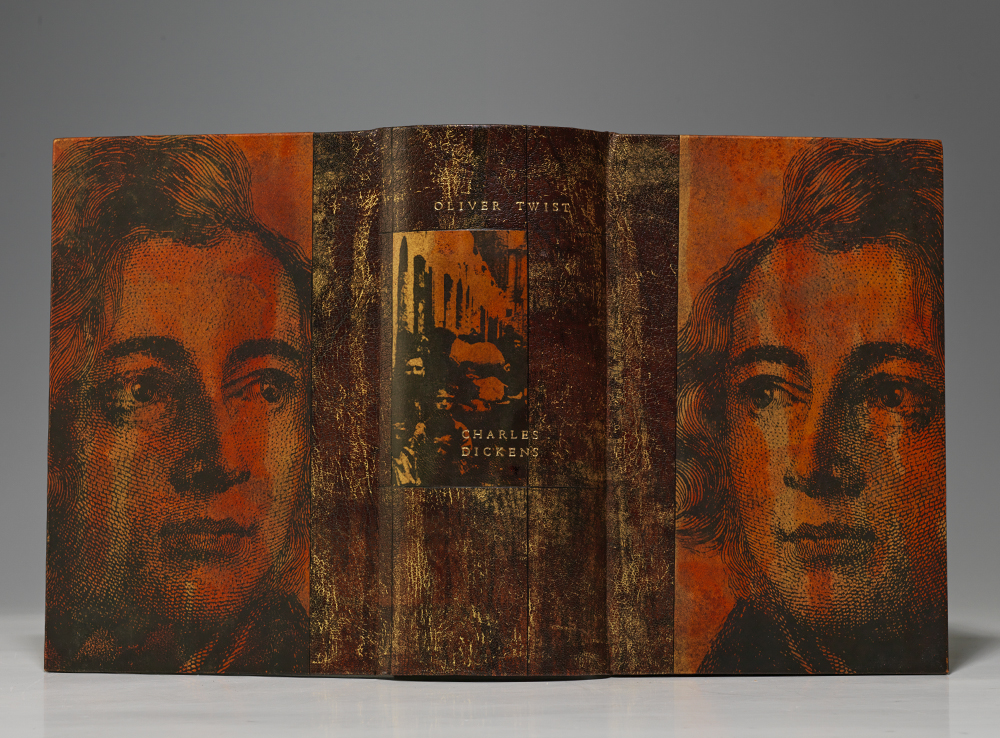

DICKENS, Charles. Oliver Twist; Or, the Parish Boy’s Progress. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841. Three volumes. Octavo, original blind-stamped purple cloth, uncut. Housed in custom chemise and half morocco slipcase.

Third edition of Dickens’ classic, the first edition to contain his important Author’s Introduction, superb presentation-association copy, inscribed by Dickens to his close friend William Charles Macready on the title page: “W.C. Macready from his affectionate friend Charles Dickens, Christmas 1841.” The actor and theatre manager Macready was for Dickens “always a particularly loved and honored friend” (ODNB), and “the most famous Shakespearean actor of his day” (Ackroyd), who dominated the English stage throughout the 1820s and 1830s.

Charles Dickens and William Charles Macready were introduced by John Forster, Dickens’ future biographer, on June 16, 1837. Macready was “already the most famous Shakespearean actor of his day, and someone for whom Dickens would have felt immediate respect and sympathy” (Ackroyd, Dickens, 210). They immediately became close friends, as did their wives, and Dickens was soon attending Macready’s rehearsals and performances. So too, Dickens would visit Macready to read out parts of his novels as he worked on them, on occasion moving Macready to tears. Dickens dedicated Nicholas Nickleby (1839) to Macready, and in 1844, Dickens read his second Christmas book The Chimes in its entirety to Macready, an event he described in a letter to his wife Catherine: “If you had seen Macready last night—undisguisedly sobbing, and crying on the sofa, as I read—you would have felt (as I did) what a thing it is to have Power” (quoted in Ackroyd, 446). Macready was also the godfather of Dickens’ daughter Kate.

Dickens wrote to Macready on December 27, 1841, just before attending the first night of Macready’s performance as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, wishing him “Health and happiness for many years, all the merriment and peace I wish you” and sending him “my latest pieces.” The Pilgrim Edition of The Letters record these as being inscribed copies of The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge. It seems probable that the present inscribed copy of Oliver Twist, published earlier in the year, was dispatched at or around the same time (see Letters of Charles Dickens, Vol. II, p. 453). Dickens inscribed the book shortly before he and his wife left for America on January 4, 1842. Dickens left his children in the care of Macready while he was away and remained in correspondence with him during the trip. Later, Dickens gave the celebratory speech for Macready when he retired from the stage in 1851, and they remained friends until the novelist’s death in 1870.

Although he had previously inscribed a first edition, third issue copy of Oliver Twist to Macready, Dickens obviously considered this third edition copy, containing his important Author’s Introduction for the first time, important enough to warrant sending an inscribed copy to his great friend. Dickens had written his Author’s Introduction in response to numerous critics who found the characters and events in Oliver Twist too fantastic to be true. The Quarterly Review had described the novel as being “directed against the poor law and workhouse system, and in our opinion with much unfairness. The abuses which he ridicules are not only exaggerated, but in nineteen cases out of twenty do not even exist.” In his eloquent and impassioned defense of his portrayal of London’s underworld, Dickens writes: “It is, it seems, a very coarse and shocking circumstance that some of the characters in these pages are chosen from the most criminal and degraded of London’s population; that Sikes is a thief, and Fagin a receiver of stolen goods; that the boys are pickpockets and the girl is a prostitute… It appeared to me to draw a know of such associates in crime as really do exist; to paint them in all their deformity, in all their wretchedness, in all the squalid poverty of their lives; to show them as they really are, for ever skulking uneasily through the dirtiest paths of life, with the great, black, ghastly gallows closing up their prospect… it appeared to me to do this, would be to attempt something that was greatly needed, and which would be a service to society… It is useless to discuss whether the conduct and character of [Nancy] seems natural or unnatural, probable or improbable, right or wrong. IT IS TRUE. Every man who has watched these melancholy shades of life know it to be so… It involves the best and worst shades of our common nature; much of its ugliest hues, and something of its most beautiful; it is a contradiction, an anomaly, an apparent impossibility, but it is truth.”

Oliver Twist was first published serially between February 1837 and April 1839 in Bentley’s Miscellany, and as a three-volume book by Richard Bentley in 1838 (six months before the initial serialization was complete). “Of the works of all great British authors of the 19th century who wrote on the social ills of the time, few can reach the same level of eloquence as Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens. In this book, Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that had never since been approached, and was labelled by many critics and readers as a subversive writer, a radical, and, one may say, a rebel. Lord Chamberlain banned the book and considered it ‘dangerous to public peace’ (Bolton, 1987), while the Regius Professor at Edinburgh saw it as ‘dangerously frank’ (Aytoun, 1864), and Lady Carlisle commented on it saying ‘I know there are such unfortunate beings as pickpockets and street walkers… but I own I do not much wish to hear what they say to one another’ (Ford, 1955). Despite that, the book was reviewed overwhelmingly with admiration. It was read as a work of art, and the young Queen Victoria found it excessively interesting’ (Collins, 1971). How did Dickens manage to do that? The answer lies in his dichotomous formula for social reform which condemns the sin and tries to redeem the sinner. He managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more than this, the very people he attacked tolerated him so completely that he became a national institution himself” (Taher Badinjki). With 24 etched plates by George Cruikshank, including frontispieces. Smith, I: 37. Gimbel A29. Sadleir 696b. This copy has extraordinary provenance, having been in the collections (and retaining the bookplates) of several important book collectors, including Comte Alain de Suzannet, Kenyon Starling, and William E. Self.

Light browning to a few plates only, scattered foxing. Inner paper hinges with short superficial splits, spines lightly sunned, extremities a bit rubbed. A lovely, near-fine copy, most rare and desirable inscribed and presented by Dickens to an important friend at Christmastime.