Description

“THE MOST RADICALLY DEMOCRATIC FRAME OF GOVERNMENT THAT THE WORLD HAD EVER SEEN”: EXCEEDINGLY RARE AND IMPORTANT FIRST EDITION OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMON-WEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, 1776, PRIMARILY AUTHORED BY BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, ONE OF ONLY 400 COPIES

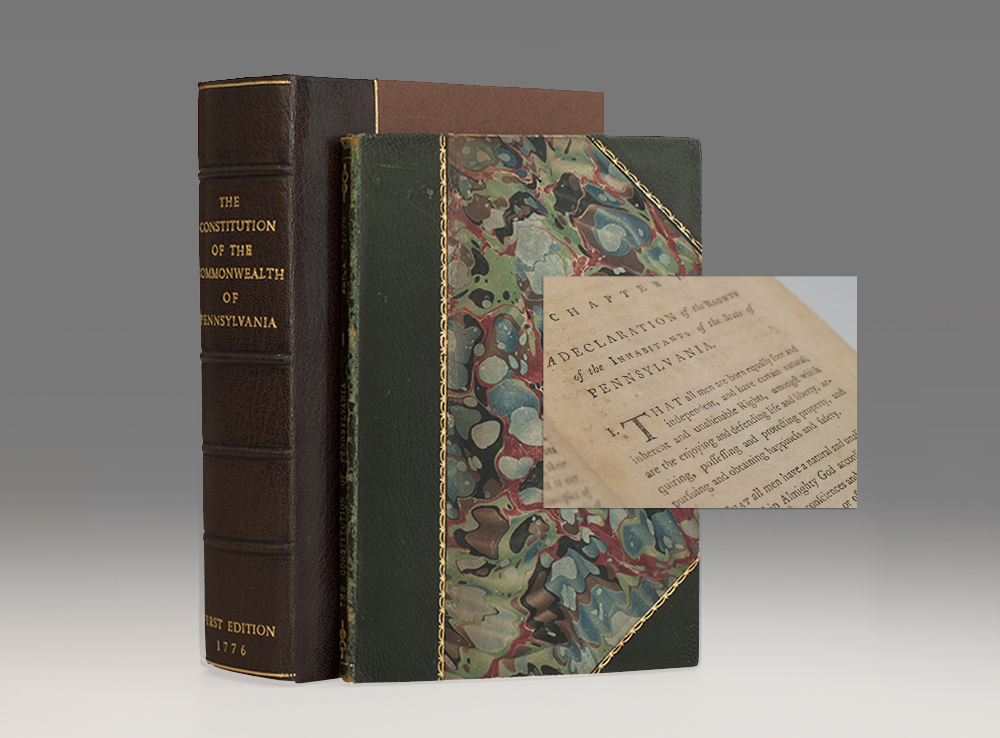

(FRANKLIN, Benjamin). The Constitution of the Common-Wealth of Pennsylvania, As Established by the General Convention for the Purpose, And Held at Philadelphia, July 15th, 1776, And Continued by Adjournments to September 28, 1776. Philadelphia: Printed by John Dunlap, 1776. Slim octavo, 19th-century three-quarter green morocco, marbled boards and endpapers; pp. 32. Housed in a custom clamshell box.

Exceptionally rare and important first edition of this foundational Pennsylvania Constitution, forged by Franklin and two fellow delegates within weeks of the Declaration of Independence, directly inspired by the Declaration and predating the federal Constitution by over a decade, a powerful influence on America’s Bill of Rights and a document that stands as a “bold statement of the framers’ commitment to the ideals of the American Revolution,” handsomely bound.

In July 1776, Pennsylvania state delegates gathered less than two weeks after the Declaration of Independence. Meeting in Independence Hall where the “Second Continental Congress was debating the new Articles, Pennsylvania was holding its own state constitutional convention. Benjamin Franklin was unanimously chosen as its president.” Primarily authored by Franklin and two fellow delegates, this groundbreaking state constitution forged “the most radical ideas about politics and constitutional authority voiced in the Revolution found expression” (Wood 315, 226). A powerful influence on the Bill of Rights and predating the federal Constitution by over ten years, the Pennsylvania Constitution is the only state constitution created by convention— unlike those of other states’ sitting legislatures or Revolutionary congresses. Crafted in direct response to the Declaration of Independence, with nearly half of the convention’s 96 delegates in military service during the Revolution, this Constitution changed the force of history in a document “historian Richard Beeman has labeled ‘the most radically democratic frame of government that the world had ever seen” (McCurdy, Origins of Universal Suffrage). This Constitution importantly owed Franklin its most controversial element— a unicameral legislature. For, to Franklin, a bicameral legislature was an alarming “vestige of the aristocratic and elitist system against which America was rebelling. Franklin likened a legislature with two branches to ‘the fabled’ snake with two heads… His fingerprints were also visible in the list of qualifications that Pennsylvania’s officeholders must meet: unlike in other states, they did not have to own property” (Isaacson, 315). Franklin and the delegates also determined that there would be a “plural executive of 12 men, one of whom would preside and thus be called ‘president… Elections were annual, voting was by secret ballot, legislative sessions were open to the public and no representative could serve for more than four years out of any seven.”

Another crucial innovation of the Pennsylvania Constitution was the abolition of property requirements in determining that “all freemen who paid taxes, and their adult sons living at home, could vote” (Murrin et al., Liberty Equality, 232-33). That “broad expansion of the electorate… marks the origins of universal suffrage in the United States.” To John Adams and others, this expansion was a dangerous slippery slope that proved “‘you ought to admit women and children.’ Adams’ criticism was prophetic… The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 had a profound effect on the United States… The document and its suffrage requirements remain a bold statement of the framers’ commitment to the ideals of the American Revolution” (McCurdy). Further, Franklin’s unicameral legislature triggered explosive debate that eventually shaped the federal Constitution. Opponents argued that a unicameral legislature subverted “what the Continental Congress had declared to be the only effective mode ever invented to promote freedom— having the several powers of government ‘separated and distributed into different hands, for checks one upon another… In the years after 1776, when the problems of politics seemed new and different from what had been expected… the idea of separation of powers assumed major significance… [becoming] the dominant principle of the American political system.”

Historians agree that “the Constitution Pennsylvanians framed in the summer of 1776 was no mere carry-over of the provincial charter… in fact it was resolved ‘to reject every thing… to clear away every part of the old rubbish… The result was the most radical constitution of the Revolutionary era, which everyone— supporters and critics alike— regarded as a monumental experiment in politics. It was ‘a radical reformation” (Wood, 449-50, 226-7). “On September 5, 1776 [the Philadelphia] convention ordered 400 copies of its proposed frame of government ‘printed for public consideration’; the consideration of the constitution was resumed by the convention on September 16, and it was adopted on September 28” (Dodd, Revision and Amendment of State Constitutions, 15-16). Printed by John Dunlap, printer of the first broadside printing of the Declaration of Independence, the first edition of the Pennsylvania Constitution is extremely rare. OCLC seems to list only microform entries for the first editions. We can locate copies at the American Antiquarian Society, the John Carter Brown, Library of Congress, the Library Company, American Philosophical Society, New York Public and Bowdoin. The Eberstadts offered the only copy that we have been able to identify on the market in the last 50 years in their Constitution catalogue in 1964, with no copy recorded at auction during that period. Sabin 60014. Evans 14979. Eberstadt 166:127. Hildeburn 3350. Harvard Tercentennial Exhibition 49. Evidence of bookplate removal.

Front inner paper hinge starting, closed marginal tear to page 9, a couple tiny holes to page 31, only light embrowning to text. A most attractive copy of a rare and important work.