Description

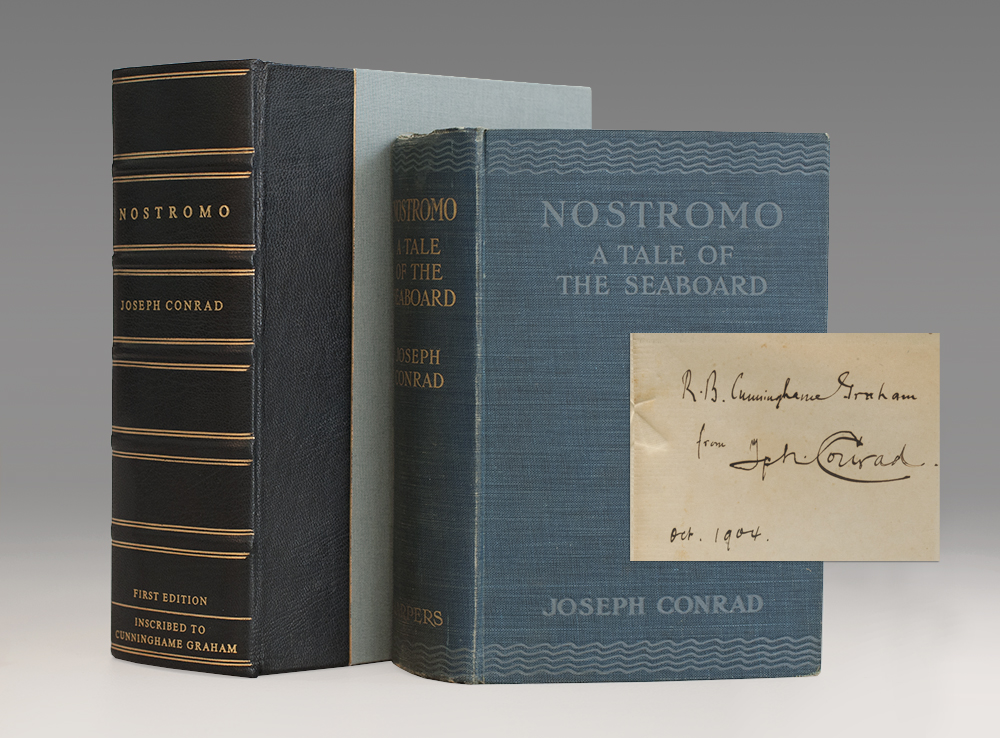

FIRST EDITION OF CONRAD’S NOSTROMO, INSCRIBED BY CONRAD IN THE MONTH OF PUBLICATION TO HIS CLOSE FRIEND R.B. CUNNINGHAME GRAHAM, THE BASIS FOR THE CHARACTER OF CHARLES GOULD IN THE NOVEL

CONRAD, Joseph. Nostromo. A Tale of the Seaboard. London and New York: Harper & Brothers, 1904. Octavo, original blue cloth. Housed in a custom clamshell box.

First edition, presentation/association copy of one of Conrad’s most important novels, inscribed on the front free endpaper in the month of publication to one of Conrad’s closest friends, the dedicatee of his book Typhoon, and the probable basis for the character of Charles Gould, “R.B. Cunninghame Graham from Joseph Conrad Oct. 1904.

Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham was a Scottish writer and traveler with an insatiable appetite for adventure. He spent years in South America as a cowboy and rancher, much of it during the continent’s political unrest. He was a socialist who was passionate about politics—Graham was a member of the House of Commons, a founding member of the Scottish Labour party, and went on to become the president of the Scottish National party. Graham first wrote to Conrad in 1897, and they enjoyed a lively correspondence from that time until Conrad’s death in 1924. In 1903, Conrad dedicated Typhoon and Other Stories to Graham, and Graham in return dedicated his 1905 work Progress to Conrad.

Conrad set Nostromo in the fictitious South American country of Costaguana, with a government run by the dictator Ribiera, a silver mine owned by Charles Gould, and Nostromo, a head longshoreman trusted by Gould for his perceived incorruptibility. It was the first time he used a location that was unfamiliar to him, so much research was to be done. Undoubtedly he deferred to Graham’s intimate knowledge of South America, relying on his first-hand stories as well as his published writings about the region, notably “Cruz Alta” from Thirteen Stories (1900), A Vanished Arcadia (1901), and Hernando de Soto (1903). Graham’s socialism, in stark contrast with Conrad’s conservative views, also influenced the tone of the novel. Nostromo is a critique of Europe’s industrial and imperialistic ventures in the South American countries.

This influence is well-documented in letters Conrad wrote to Graham during the writing of Nostromo: 9 May 1903: “I want to talk to you of the work I am engaged on now. I hardly dare avow my audacity—but I am placing it in Sth [sic] America in a Republic I call Costaguana. It is however concerned mostly with Italians.” 8 July 1903: “I am dying over that cursed Nostromo thing. All my memories of Central America seem to slip away. I just had a glimpse 25 years ago—a short glance. That is not enough pour bâtir un roman dessus. … When it’s done I’ll never dare look you in the face again.” 7 October 1904: “I forgive you (generously) the treacherous act of looking at a fragment of Nostromo. On your side you must (generously) forgive me for stealing and making use of in the book of your excellent “y dentista” anecdote. The story comes out on Thursday next. Don’t buy it. I’ll send you a copy of—and in due—course. I expect as of right and in virtue of our friendship an abusive letter from you upon it; but I stipulate a profound and unbroken secrecy of your opinion as before everybody else. I feel a great humbug.” Graham himself wrote to Edward Garnett, publisher at Duckworth:

15 October 1904: “‘Nostromo’ is, as far as I have seen by bits of it (not a fair way to test a book), perhaps not quite his highest level. But his second best is better than most peoples’ best.” Garnett reviewed Nostromo in the Speaker in November 1904, in which his praises and critiques mirror Graham’s comments.

Years later, in Conrad’s obituary essay, published in Saturday Review, Graham wrote of Nostromo: “‘Nostromo’, with its immortal picture of the old follower of Garibaldi, its keen analysis of character, and the local colour that he divined rather than knew by actual experience, its subtle horror and the completeness of it all, forming an epic, as it were, of South America, written by one who saw it to the core, by intuition, amazed me just as it did when I first read it, Consule Planco, in the years that have slipped past.” Sir John Lavery’s portrait of Cunninghame Graham was used for many years as the cover illustration for the Penguin Classics edition of Nostromo. It is believed that this first edition consisted of about 2000 copies. Wise 15. Cagle A10a.1.

Text with scattered foxing to first and last few leaves and edges of text block only. Only very mild wear to spine extremities of unusually fresh cloth.