Description

THOMAS JEFFERSON—“THE TRUE GROUND ON WHICH WE DECLARE THESE ACTS VOID IS THAT THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT HAS NO RIGHT TO EXERCISE AUTHORITY OVER US”: A STERLING COLLECTION OF FIRST PRINTINGS OF THE MOST IMPORTANT BRITISH ACTS—THE 30 LAWS THAT SPARKED AND OPPOSED AMERICA’S REVOLUTION, FEATURING THE COMPLETE SERIES OF TOWNSHEND ACTS, INTOLERABLE ACTS AND CONCILIATORY ACTS, AND VERY RARE FIRST PRINTINGS OF THE SUGAR ACT, TEA ACT, THE INCENDIARY STAMP ACT AND THE REPEAL OF THE STAMP ACT

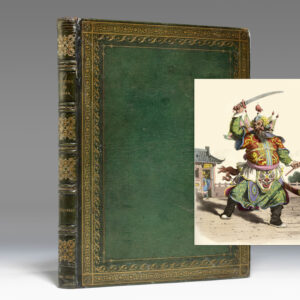

AMERICAN REVOLUTION. Revolutionary War Acts. Thirty Acts: 1764-1783. London: Mark Baskett / Charles Eyre and William Strahan, 1764-67 / 1770-83. Folio, each act in period style marbled wrappers, each complete with title page as issued. Housed in a custom clamshell box.

An extraordinary and complete collection of rare first printings of the most important British laws that inflamed and ultimately acknowledged America’s will toward independence, an assemblage of 30 pivotal Revolutionary Acts that record imperial authority and colonial resistance in legislation such as the Declaratory Act (1766), the Quartering Acts of 1765-6, the Townshend Acts (1767), the Intolerable Acts (1774), the Quebec Act (1774), the American Prohibitory Act (1776) and the Conciliatory Acts (1778). With the extremely rare first printings of the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765), the Repeal of the Stamp Act (1766) and the Tea Act (1773), less than 1100 copies of each act printed.

This unparalleled collection of 30 Revolutionary War Acts offers landmark evidence that the American Revolution primarily emerged from a contest between the often ill-conceived actions of the British Parliament and the response of American colonists—a population once certain that Parliament was “the bulwark of their liberties” who came to echo Franklin’s conviction that “time was emphatically not on Britain’s side” (Schama, 461). This stellar assemblage unites rare first printings of the Revolution’s most crucial parliamentary acts—in particular the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765), the Repeal of the Stamp Act (1766) and the Tea Act (1773), together with the incendiary Quartering Acts of 1765-5, the Townshend Acts (1767), the Intolerable Acts (1774) and the 1776 American Prohibitory Act. Also included here are the rarely found Conciliatory Acts (1778) and wartime laws on prisoners, high treason, piracy and acts that repeal those very laws that first splintered colonial loyalties—legislation that ultimately heralds American independence.

Parliament’s powerful role in the coming Revolution first emerged when it sought to bring the colonies into line with “a new substantial duty on the foreign commodity most in demand in America”—sugar (Schama, 456). But colonials saw in that law “the thin end of a wedge of ‘taxation without representation’” and this “‘one single Act of Parliament,’ wrote James Otis, ‘has set people a-thinking’” (Morison, xiii-iv). When Parliament followed with another revenue bill, however, few guessed that their newly forged Stamp Act (1765) would “inaugurate the beginning of the end of British America” (Schama, 457). “David Ramsay, one of the first historians of the Revolution… called the Stamp Act‘the hinge of the Revolution,’ and so it certainly was” (Smith I:250). Patrick Henry “compared the introduction of the stamps to the most iniquitous Roman tyranny” (Schama, 459), and the Stamp Act Congress convened to debate America’s response, while in Britain William Pitt accused his country of sheathing “the sword not in its scabbard, but in the bowels of your countrymen” and demanded “that the Stamp Act be repealed absolutely, totally and immediately.” Yet ultimately that repeal proved fruitless, especially when Britain continued to resist the lessons of history and immediately “passed the Declaratory Act… [restating] Parliament’s rights to make binding laws for the colonies” (Langguth, 85).

When news of the Repeal of the Stamp Act (1766) reached America, cities erupted in celebration. Within a year, however, Charles Townshend, a strong supporter of the Stamp Act, “turned again to the idea of an American tax. But this time he would hold the colonists to their word” (Langguth, 92). He demanded tighter control over American customs and when New York quarreled with the 1766 Quartering Act, retaliated with the Restraining Act (1767). Colonists responded to his series of Townshend Acts “by mobilizing a boycott of British imports” (Schama, 462) and “a new period of agitation began” (Morison, xv). This outstanding collection continues its unfolding of the awakening Revolution not only with these pivotal laws, but also its inclusion of the 1770 Repeal of the Townshend Revenue Act, the Quebec Act (1774) and the Tea Act (1773), which incited yet another battle over taxation without representation. To Benjamin Rush, British ships entering Boston harbor, filled with tea, contained “‘something worse than death—the seeds of SLAVERY’… Boston instantly turned into a revolutionary hothouse” that produced, on one memorable October night, the legendary Boston Tea Party. To John Adams, the patriots’ “Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences and so lasting, that I cannot but consider it as an Epocha [sic] in History’” (Schama, 469). Britain countered with the Intolerable Acts (1774)—“inflaming English public opinion, strengthening the ‘die-hard’ element in Cabinet and Parliament, and producing an unwise attempt at punishment and cure… but instead of isolating Massachusetts, as had been hoped, these Acts demonstrated a parliamentary power more dangerous to colonial liberty than mere taxing: and thus rallied 12 continental colonies to Massachusetts” (Morison, xxxiv).

War began on April 19, 1775 at Lexington and Concord and, as America began its long struggle for independence, Parliament issued the American Prohibitory Act of 1776, at once signaling the end of any hope of reconciliation and the beginning of the war in earnest. Along with that law, this collection further includes important wartime acts, such as that authorizing ship commanders to “take or make Prize” of enemy ships, and the High Treason Act and the Captures Act, all passed in 1777, together with a law on prisoners of wars and the Peace Act of 1782. As American independence loomed, a series of belated, ineffectual conciliatory acts were passed—and in 1783 Parliament acknowledged its former colony, for the first time, as “the United States of America.” First editions, first printings, of 30 Revolutionary War acts from the Sessional Volumes of Parliament, preceding all American printings. Acts printed prior to 1796 are extremely scarce, since the maximum number printed was only around 1100 copies (see Report of the Committee for the Promulgation of the Statutes, 1796).

Very light scattered foxing. A truly outstanding, about-fine collection of Revolutionary War acts.