Description

EXCEEDINGLY RARE FIRST EDITION OF HAMILTON’S PUBLIC CREDIT REPORT, HIS CONTROVERSIAL FIRST REPORT AS SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY, A WORK OF “HISTORIC RENOWN” WHOSE CONTROVERSIAL VISION FOR RESOLVING REVOLUTIONARY WAR DEBT SPARKED THE TWO-PARTY SYSTEM, A CORE DOCUMENT IN AMERICA’S POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SYSTEM

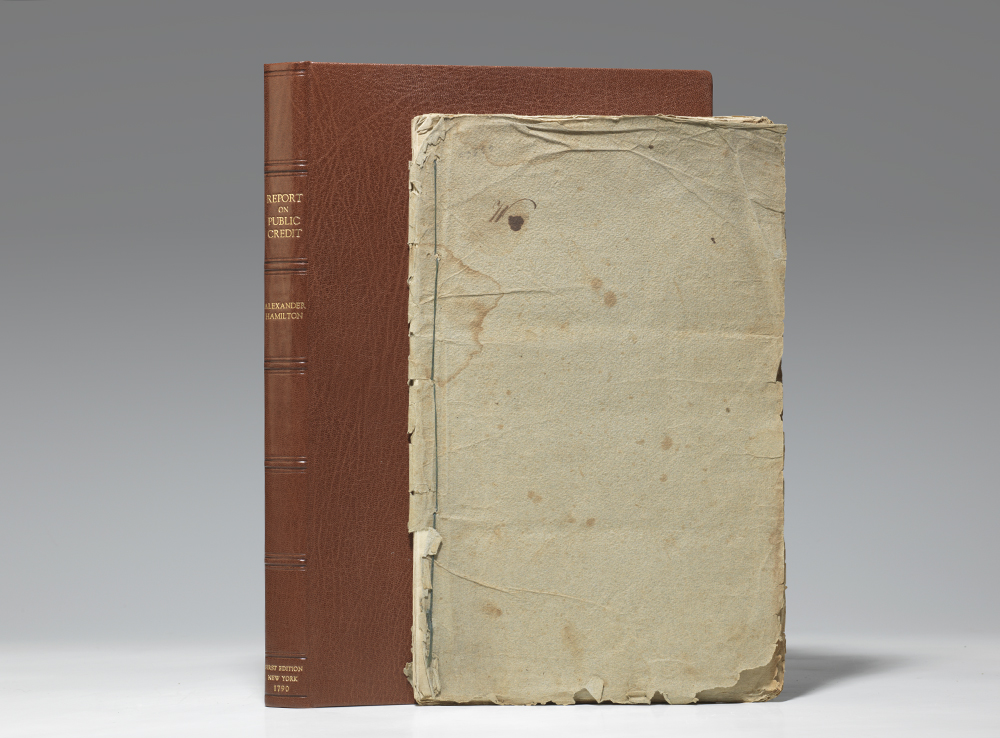

(HAMILTON, Alexander). Report of the Secretary of the Treasury to the House of Representatives, Relative to a Provision for the Support of the Public Credit of the United States, In Conformity to a Resolution of the Twenty-First Day of September, 1789. Presented to the House on Thursday the 14th Day of January, 1790. New York: Printed by Francis Childs and John Swaine, 1790. Folio (8-1/2 by 13-1/2 inches), contemporary blue-gray wrappers, early stitching, uncut; pp. [1-3], 4-51, [1]. Housed in a custom half morocco folding case.

Rare first edition of Hamilton’s electrifying Report… of the Public Credit, one of the greatest American state papers, his first report as America’s first Secretary of the Treasury, presenting an seminal vision for the federal government’s fiscal role that ultimately laid ‘the groundwork for a great nation” (Chernow). Here Hamilton, amidst fierce partisanship that sparked the creation of a two-party political system, outlined his plan for the federal government to absorb millions of dollars of state debts incurred by the Revolution, a document central to the creation of America’s political and governmental system. This copy with an important provenance in containing the contemporary ownership signature on the rear wrapper of William Imlay, whose work for the United States War Department included the repayment of states’ Revolutionary War debts, making Hamilton’s Report central to his field, dated by Imlay, “December 1 1800.” A virtually unobtainable landmark publication in contemporary wrappers with a significant provenance.

Shortly after his appointment as Secretary of the Treasury on September 11, 1789, Hamilton, co-author of The Federalist Papers, was asked by the House to prepare a plan for restructuring the web of state and national debt left by the Revolution. He quickly went to work on “the giant task that engrossed him that fall: the Report… of the Public Credit that Congress wanted by January. He had to sum up America’s financial predicament and recommend corrective measures to deal with the enormous public debt… As with his 51 Federalist essays, he put in another sustained bout of solitary, Herculean labor,” and carefully reviewed the works of Hume, Montesquieu, Hobbes and Postlethwayt. But had Hamilton stuck only “to dry financial matters, his Report would never have attained such historic renown. Instead he presented a detailed blueprint of the government’s fiscal machinery, wrapped in a broad political and economic vision. From the opening pages Hamilton reminded readers that the government’s debt was the ‘price of liberty’ inherited from the Revolution,” and he rigorously addressed how the debt was to be funded and structured. At the beginning of the second session of Congress, Hamilton sought to present his plan in a speech, but was denied the opportunity, setting a precedent for cabinet members not to appear before the full House of Congress. Instead, given fears of the executive branch exceeding its grasp, he was required to submit his plan in writing. Almost immediately afterward, Hamilton’s “magnum opus… had an electrifying effect” generated by fierce partisanship. “His vision, however, was fixed on America’s future… he was laying the groundwork for a great nation” (Chernow, 295-321).

According to Hamilton’s biographer, Robert Hendrickson, “This first of Hamilton’s great public reports… constituted the seven-point legislative program of President Washington’s first administration. The seven points were: 1) the restoration of public credit, 2) a sound system of taxation, 3) a national bank, 4) a sound currency, 5) the promotion of commerce, 6) a liberal immigration policy, and 7) the encouragement of manufactures.” Parts of this program were elaborated in subsequent Hamilton reports, but the kernels of them all, and particularly the first two, are in this first Report. On February 8, 1790, as the House began to debate this Report, partisan lines quickly formed between those who applauded his proposals and those who saw in them “deep, dark, and dreary chaos,” as Fisher Ames put it. Enmity over Hamilton’s “plan to have the federal government assume the 25 million dollars of state debts… [which] Jefferson later categorized as ‘the most bitter and angry contest ever known in Congress,” was heightened on February 24, when Madison pointedly opposed the assumption of unequal state debts, an action seen by Hamilton as “a painful personal betrayal… This falling-out was to be more than personal, for the rift between Hamilton and Madison precipitated the start of the two-party system in America” (Chernow, 321, 304). In addition to Hamilton’s plan for the federal government to absorb many of the state debts of the Revolution, as well as old Continental war loans and certificates given to soldiers, he proposed that foreign debts be honored, and all would be consolidated into one national debt that would be funded, establishing public credit. Privately Hamilton felt that the consolidated debt would be the glue which would hold the nation together. Yet the subsequent political divide led him to grimly forecast the Union’s collapse and prompted Jefferson, that June, to broker a “political bargain of decidedly far-reaching significance”— wherein “Madison agreed to permit the core provision of Hamilton’s fiscal program to pass; and in return Hamilton agreed to use his influence to assure that the permanent residence of the national capital would be on the Potomac River” (Ellis, 49).

Hamilton’s plans stepped on a variety of state, sectional and personal interests, but in the end, the essence of Hamilton’s Report was adopted and the fiscal basis of the federal government was laid. Evans 22998. Ford 161. Henrickson, Hamilton II:21-25. Church 1253. This copy bears the contemporary inked ownership signature on the rear wrapper of “William Imlay December 1 1800,” along with a contemporary inked “W” to the front wrapper. Imlay was a clerk in the United States War Department, stationed in Connecticut in the 1780s and 1790s. He had a wide variety of duties, including working with the Continental Loan Office in repaying Revolutionary War debts owed to states and private citizens. In such a capacity, Hamilton’s public credit Report was central to his work. Small bookplate to inner front cover of folding box.

Wrappers with some old stains and edgeworn, spine partly perished. Very clean and fresh internally. A lovely copy in original unsophisticated condition.